Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

Cowpox (Orthopoxvirus)

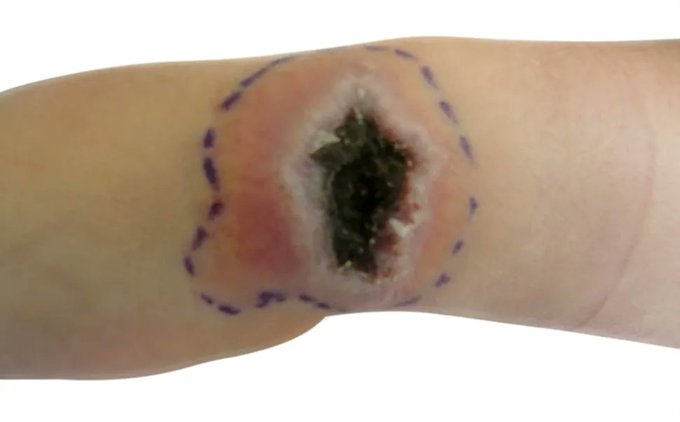

🧠 Cowpox is a zoonotic Orthopoxvirus infection that usually causes a single, painful ulcer/vesico-pustular lesion that evolves into a black eschar with regional lymphadenopathy. In the UK it’s rare, but classically follows contact with cats that hunt rodents (or direct rodent exposure), and it can be mistaken for bacterial infection or even anthrax if you don’t think “pox”. :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

🦠 What is cowpox?

- Cause: Cowpox virus (CPXV), an Orthopoxvirus (same genus as smallpox and mpox).

- Reservoir: mainly wild rodents; “cowpox” is a historical name—humans often acquire it indirectly via domestic cats that catch rodents.

- Why it matters: Most cases are self-limiting, but severe disease can occur in immunosuppressed patients or with ocular involvement.

Pathophysiology pearl: orthopoxviruses replicate in the cytoplasm and trigger a strong local inflammatory response; the characteristic necrosis/eschar reflects viral cytopathic effect plus host immunity, while regional nodes reflect antigen drainage and immune activation. :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

🧭 UK epidemiology & transmission

- In the UK/Europe: human cases are uncommon; when they do occur, they’re often linked to cat contact (scratches/bites) or rodent exposure.

- Seasonality: tends to cluster around periods when rodent exposure is higher (often late summer/autumn in European reports).

- Spread: usually via direct inoculation into broken skin; person-to-person spread is not the typical pattern for cowpox, but lesion material is infectious.

In England, cowpox is not listed among statutory notifiable diseases (mpox and smallpox are). If you’re worried about broader public health risk, you can still discuss with your local health protection team as an “other significant disease”. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

🩺 Clinical features (humans)

- Incubation: typically about 8–12 days.

- Primary lesion: starts as a macule/papule → vesicle/pustule → ulcer with black eschar (often on hands/forearms/face).

- Local signs: surrounding erythema, swelling, pain, and regional lymphadenopathy are common.

- Systemic symptoms: fever/malaise may occur.

- Natural course: slow healing over weeks; scarring can occur.

“Think cowpox” when you see a poorly healing eschar plus tender nodes after a cat scratch—this pattern is a classic trap for repeated antibiotics or unnecessary procedures. :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

🚩 Red flags / higher-risk situations

- 🛡️ Immunosuppression (e.g., high-dose steroids, chemo, transplant, advanced HIV): risk of extensive/disseminated disease.

- 👁️ Eye involvement (peri-orbital lesions, conjunctivitis, vision symptoms): can be serious—urgent specialist input.

- 🌡️ Marked systemic illness, rapidly progressive lesions, or extensive skin involvement.

🧪 Investigations

- Best test: PCR for orthopoxvirus DNA from a swab of the lesion base or scab material (discuss with microbiology/virology).

- Histology: may show viral cytopathic changes but is not definitive without virology.

- Avoid pitfalls: bacterial swabs may grow secondary colonisers; don’t let that distract you from the primary diagnosis.

Diagnosis is typically confirmed by PCR on lesion/scab samples. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

🩹 Management (practical)

- Supportive care is usually sufficient: analgesia, simple dressings, keep lesion clean and covered.

- Treat secondary bacterial infection only if there are convincing signs (spreading cellulitis, purulence with systemic features).

- Specialist advice (ID/virology/dermatology) for immunosuppressed patients, extensive disease, or ocular involvement.

- Antivirals: in severe orthopox infections, agents such as tecovirimat may be considered via specialist pathways.

Orthopox antiviral options (including tecovirimat) are discussed in specialist literature and are typically reserved for severe/high-risk disease. :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

🧼 Infection prevention & patient advice

- 🧤 Cover lesions; avoid touching/scab picking; wash hands after dressing changes.

- 🧺 Don’t share towels/bedding until lesions have crusted/healed; launder normally but carefully handle contaminated dressings.

- 🐱 If linked to a pet cat with lesions, advise veterinary assessment and minimise direct contact with the cat’s lesions.

- 🏥 In healthcare: use contact precautions when handling lesions/dressings; discuss with IPC if uncertain.

🔍 Differentials you should actively think about

- 🐑 Orf (parapoxvirus) — after sheep/goat exposure; similar “farmyard finger” lesions.

- 🧫 Staph/Strep skin infection — usually lacks the staged pox evolution and prominent nodes.

- 🕷️ Spider/insect bites — often overcalled; course is different.

- ☣️ Cutaneous anthrax — painless eschar with significant oedema; exposure history is key (and it’s notifiable/urgent).

- 🧬 Mpox — tends to be more generalised with systemic prodrome and epidemiological risk factors.

🧠 History link (why “vaccination” exists)

Cowpox (and related animal poxviruses) famously provided cross-protection against smallpox, underpinning the concept of vaccination—although the modern smallpox vaccine uses vaccinia virus, which is related but distinct. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

🩺 Mini-cases (for teaching)

- 👨🌾 “Farmyard finger”: painful pustule → black eschar on a finger after handling animals; ask about sheep/goats (orf) vs cat/rodent contact (cowpox).

- 🐾 Cat scratch + nodes: ulcer/eschar on dorsum of hand with tender epitrochlear/axillary nodes; repeated antibiotics haven’t helped → send orthopox PCR.

- 👁️ Peri-orbital lesion: eyelid pustule/eschar with conjunctival irritation after cat contact → urgent ophthalmology + ID/virology input.

✅ One-liner to remember: “Eschar + lymph nodes + cat/rodent exposure = think cowpox; confirm with PCR, treat mainly supportively, and escalate early if immunosuppressed or eye involvement.” :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

Categories

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology