| Download the amazing global Makindo app: Android | Apple | |

|---|---|

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: Educational use only. Not for diagnosis or management. See below for full disclaimer. |

Lateral Medullary Syndrome

Related Subjects: |Acute Stroke Assessment (ROSIER&NIHSS) |Atrial Fibrillation |Atrial Myxoma |Causes of Stroke |Ischaemic Stroke |Cancer and Stroke |Cardioembolic stroke |CT Basics for Stroke |Endocarditis and Stroke |Haemorrhagic Stroke |Stroke Thrombolysis |Hyperacute Stroke Care

Opalski theorized that weakness in Lateral Medullary Syndrome (LMS) was due to ischaemia of the lateral medulla extending to the upper cervical cord, affecting corticospinal fibers below the pyramidal decussation. This may also involve occlusion of the posterior spinal artery.

Introduction

- Lateral Medullary Syndrome (LMS), also known as Wallenberg syndrome, is a vascular syndrome resulting from arterial occlusion.

- It was named after Adolf Wallenberg, who described the syndrome in 1895, though the first description dates back to 1808 by Gaspard Vieusseux.

- Opalski syndrome, first described in 1946, is a variant of Wallenberg syndrome with ipsilateral hemiparesis, caused by the extension of ischaemia to the spinal cord.

- Etiologies of LMS can vary, including small and large vessel diseases, and can be mixed in presentation.

🧬 Aetiology

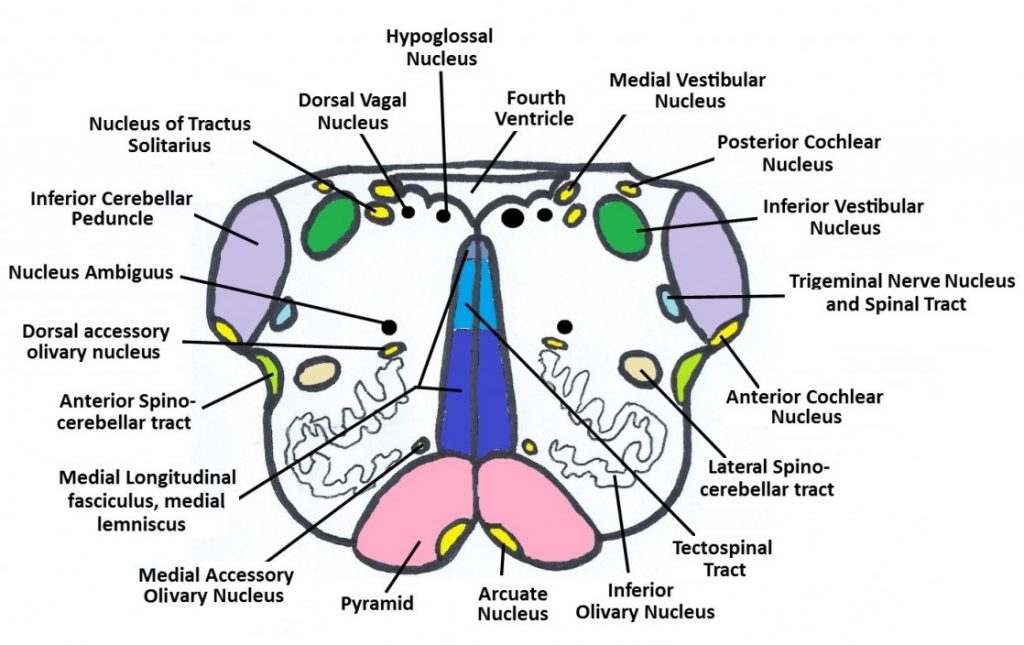

- The medulla is densely packed with important long fiber tracts, and vascular occlusion can disrupt multiple pathways.

- Occlusion of the vertebral artery (VA): The most common cause of LMS.

- Occlusion of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA): PICA occlusion can also cause LMS due to its supply to the lateral medulla.

- Occlusion of small lateral medullary perforators: Smaller vessels can cause localized damage.

- Additional etiologies include cardioembolic events, atherosclerosis, arterial dissection, and rarer causes like Moyamoya disease.

🩺 Clinical Features

- Sudden loss of swallow (Nucleus Ambiguus): Dysphagia and loss of gag reflex due to involvement of cranial nerves IX and X.

- Ipsilateral ataxia/dysmetria: Incoordination, often affecting the trunk and limbs, due to damage to the lateral cerebellum or inferior cerebellar peduncle.

- Horner's syndrome: Ipsilateral miosis, ptosis, and anhidrosis due to disruption of the descending sympathetic pathway.

- Ipsilateral hemiparesis (Opalski syndrome): A variant with weakness on the same side as the lesion.

- Ipsilateral reduced facial sensation to pain and temperature: Involvement of the descending nucleus of the trigeminal nerve (V).

- Contralateral reduced sensation in arm, trunk, and leg to pain and temperature: Due to damage to the spinothalamic tract.

- Hiccups: Possibly vagal-mediated, often persistent and difficult to manage.

- Vertigo: Related to involvement of the vestibular nuclei, causing dizziness and imbalance.

- Respiratory distress and apnea: Rare but severe complication due to medullary involvement.

- Aetiological clues: Look for neck pain or trauma (suggesting arterial dissection), atrial fibrillation (AF), hypertension, smoking, or alcohol use as contributing factors.

🔎 Investigations

- Blood tests: FBC, U&E, LFTs, ESR to assess for underlying causes and comorbidities.

- ECG and CXR: To evaluate for cardioembolic sources or other systemic conditions.

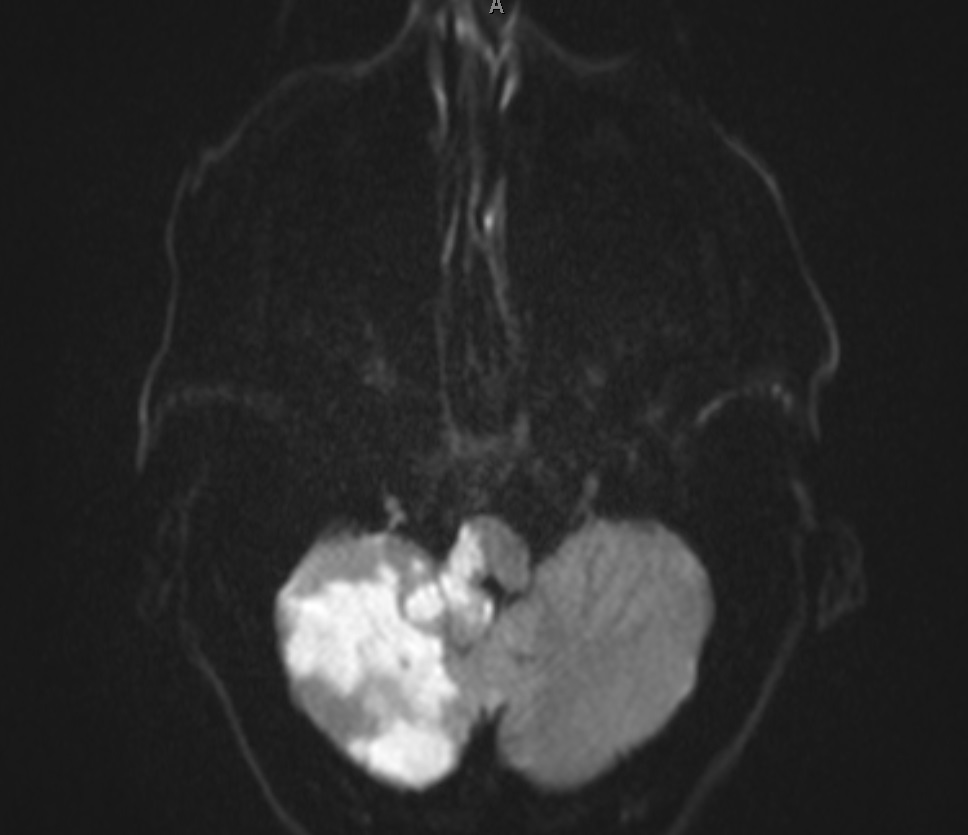

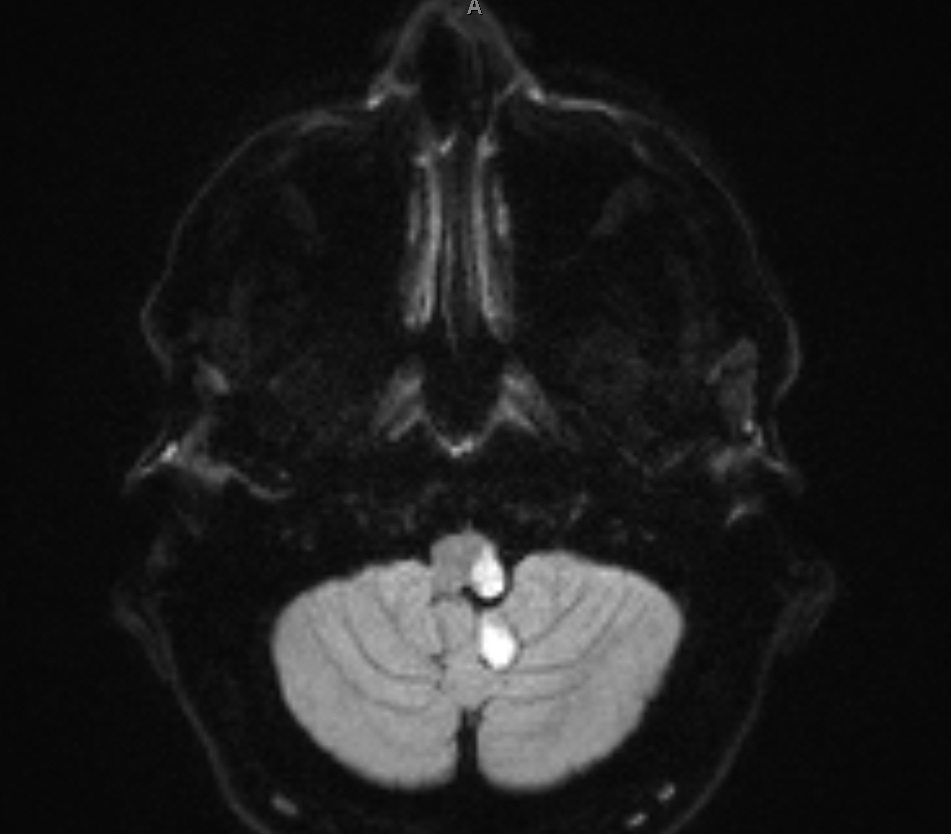

- MRI: Diagnostic tool of choice, as the lesion should be visible on imaging. However, LMS may be missed if the MRI does not extend low enough or is not carefully evaluated.

- MRA/CTA: To assess vasculature, particularly if dissection is suspected.

- Echocardiogram and Holter monitoring: (24-hour or 7-day) to detect any cardioembolic sources, especially atrial fibrillation.

💊 Management

- Initial management (ABC): Some patients may develop respiratory distress or apnea, requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation.

- Thrombolysis: Consider thrombolysis if appropriate. NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) may underreport disability, especially in patients with dysphagia, which can be severely disabling. Thrombolysis should be considered even in cases of borderline NIHSS.

- Aspirin: Start 300 mg (or 325 mg in the US) for 14 days, with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) if necessary.

- PEG tube: If dysphagia persists for over two weeks, consider a PEG tube for early discharge and nutritional support.

- Hiccups: For ongoing hiccups, consider Chlorpromazine (25-50 mg every 6 hours) or Metoclopramide (10 mg three times daily).

- Long-term management: Initiate Clopidogrel and statins. Consider monitoring for atrial fibrillation or other embolic sources, especially if large vessel occlusion (VA) is involved.

References

- Patterns of Lateral Medullary Infarction: Vascular Lesion-MRI Correlation of 34 Cases

- Opalski's Syndrome: A rare variant of lateral medullary syndrome. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013 Jan-Mar; 4(1): 102-104.

Cases — Lateral Medullary Syndrome (Wallenberg’s)

- Case 1 — Classic Presentation 🧠: A 58-year-old man with hypertension develops sudden vertigo, nausea, and unsteady gait. Exam: left-sided Horner’s syndrome, loss of pain/temperature on the left face and right body, ipsilateral limb ataxia, and dysphagia. MRI: infarct in left lateral medulla (PICA territory). Diagnosis: Lateral medullary (Wallenberg’s) syndrome due to posterior inferior cerebellar artery occlusion. Management: Stroke protocol (antiplatelet therapy, vascular risk factor control), swallow assessment, physiotherapy.

- Case 2 — Vertebral Artery Dissection ⚡: A 42-year-old man presents with acute occipital headache and vertigo after neck manipulation. Exam: right-sided limb ataxia, hoarseness, and right Horner’s syndrome. MRI/MRA: vertebral artery dissection with lateral medullary infarct. Diagnosis: Lateral medullary syndrome secondary to vertebral artery dissection. Management: Antithrombotic therapy (anticoagulation/antiplatelet depending on protocol), stroke rehab, vascular neurology input.

- Case 3 — Severe Dysphagia with Aspiration Risk 🍽️: A 67-year-old woman presents with sudden vertigo, hiccups, and difficulty swallowing. Exam: uvula deviates away from lesion side, reduced gag reflex, left Horner’s syndrome, contralateral sensory loss. MRI confirms left lateral medullary infarct. Diagnosis: Lateral medullary syndrome with severe bulbar involvement. Management: NG feeding or PEG if persistent; antiplatelets; speech and language therapy; intensive stroke rehab.

Teaching Commentary 🧠

Lateral medullary (Wallenberg’s) syndrome arises from infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) or vertebral artery. Key features: - Ipsilateral: Horner’s syndrome, facial loss of pain/temp, limb ataxia, palate weakness (dysphagia, hoarseness). - Contralateral: body loss of pain/temp (spinothalamic tract). - Other signs: vertigo, hiccups, nystagmus. Mnemonic: “Don’t PICA horse (hoarseness) that can’t eat (dysphagia).” Management: stroke protocol (antiplatelets or anticoagulation if dissection), swallow precautions, rehab. Prognosis varies: motor power often preserved but swallowing and gait issues can be long-term.

Categories

- A Level

- About

- Acute Medicine

- Anaesthetics and Critical Care

- Anatomy

- Anatomy and Physiology

- Biochemistry

- Book

- Cardiology

- Collections

- CompSci

- Crib Sheets

- Crib sheets

- Dental

- Dermatology

- Differentials

- Drugs

- ENT

- Education

- Electrocardiogram

- Embryology

- Emergency Medicine

- Endocrinology

- Ethics

- Foundation Doctors

- GCSE

- Gastroenterology

- General Practice

- Genetics

- Geriatric Medicine

- Guidelines

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Hepatology

- Immunology

- Infectious Diseases

- Infographic

- Investigations

- Lists

- Mandatory Training

- Medical Students

- Microbiology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Neurosurgery

- Nutrition

- OSCE

- OSCEs

- Obstetrics

- Obstetrics Gynaecology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Oral Medicine and Dentistry

- Orthopaedics

- Paediatrics

- Palliative

- Pathology

- Pharmacology

- Physiology

- Procedures

- Psychiatry

- Public Health

- Radiology

- Renal

- Respiratory

- Resuscitation

- Revision

- Rheumatology

- Statistics and Research

- Stroke

- Surgery

- Toxicology

- Trauma and Orthopaedics

- USMLE

- Urology

- Vascular Surgery