| Download the amazing global Makindo app: Android | Apple | |

|---|---|

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: Educational use only. Not for diagnosis or management. See below for full disclaimer. |

Arachnoid cyst

🫧 Definition: An arachnoid cyst is a benign, CSF-filled, extra-axial sac formed by splitting/duplication of the arachnoid membrane. Most are congenital and found incidentally on brain imaging.

📌 Why it matters

Arachnoid cysts are common incidental findings on CT/MRI, but a minority cause symptoms via mass effect, obstruction of CSF flow, or (rarely) rupture/haemorrhage. The clinical challenge is deciding whether the cyst is an “innocent bystander” or plausibly responsible for symptoms such as headache, seizures, focal deficits, or hydrocephalus. Most require reassurance and observation rather than intervention, but red flags mandate neurosurgical input.

🧬 Aetiology and Pathophysiology

Most intracranial arachnoid cysts are primary (congenital), arising during development when the arachnoid layers split and trap CSF-like fluid. Less commonly, secondary cysts develop after trauma, haemorrhage, infection, or surgery due to arachnoid scarring and loculated CSF spaces. Many cysts remain stable; enlargement (when it occurs) may relate to partial communication (“ball-valve” effect), CSF pulsation dynamics, or local compliance changes. Clinically, symptom generation is usually mechanical: compression of adjacent brain, cranial nerves, or CSF pathways.

- Primary (developmental): most common; often detected in childhood or young adulthood.

- Secondary (acquired): post-traumatic, post-infective, post-haemorrhagic, post-operative loculations.

- Mass effect: sulcal effacement, ventricular compression, midline shift (if large).

- CSF obstruction: hydrocephalus risk (especially suprasellar or posterior fossa).

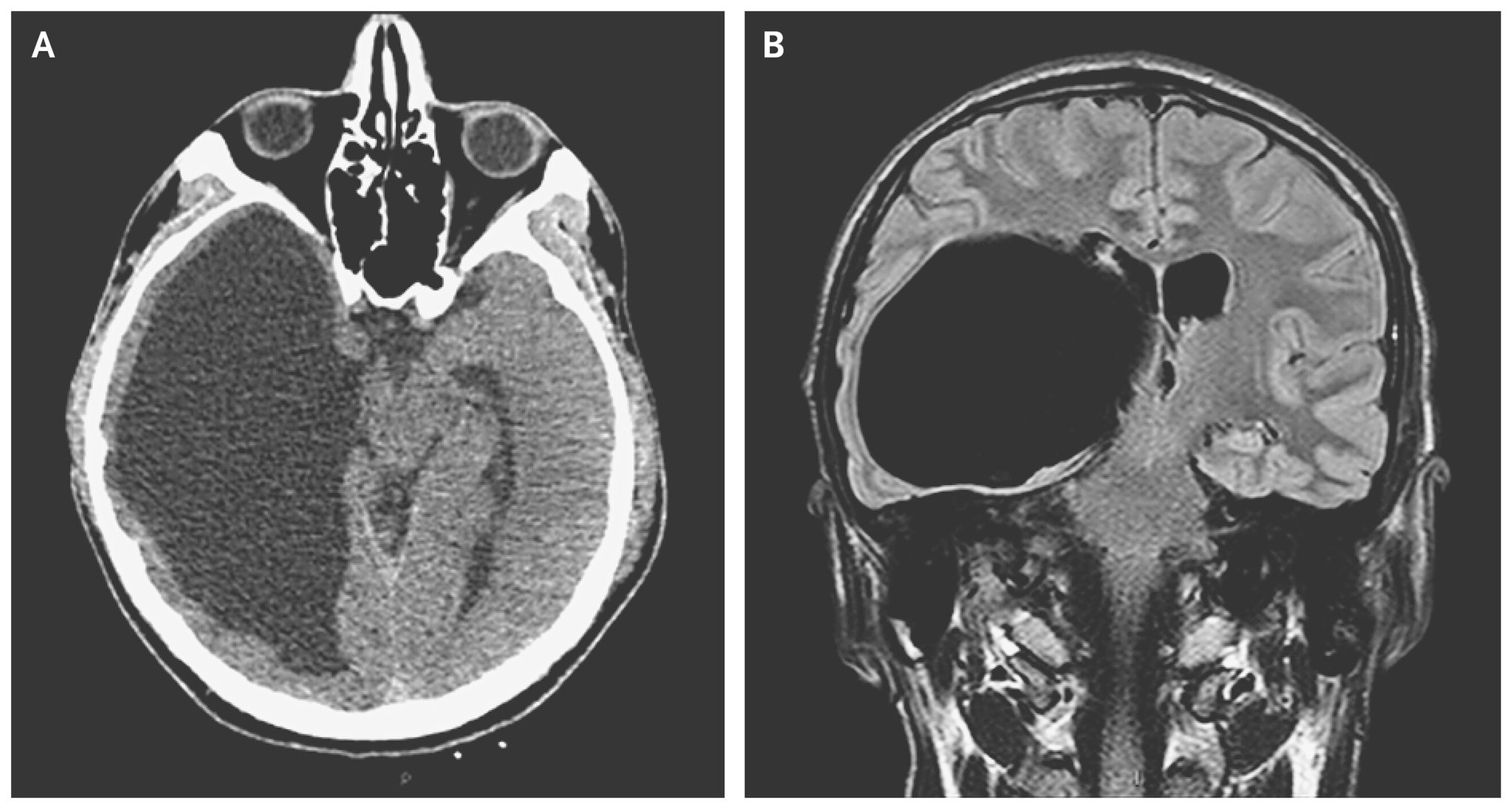

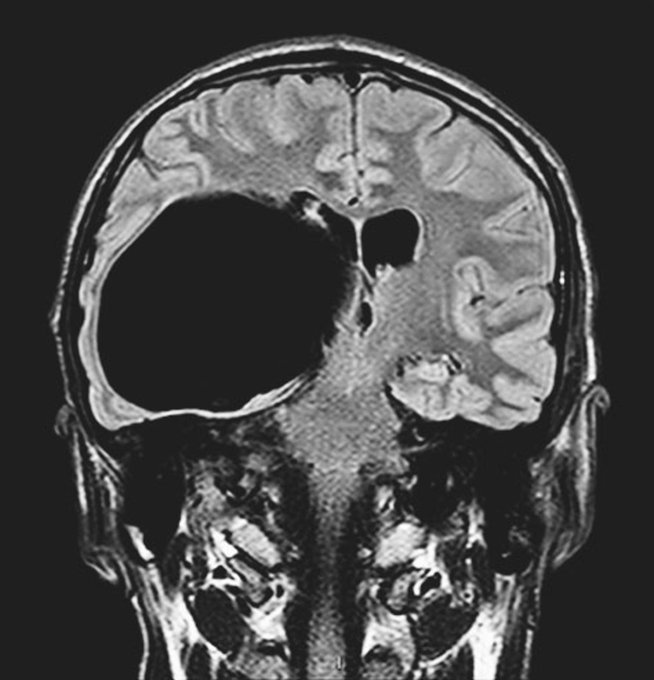

🖼️ Example Images

📍 Typical Locations and Clinical Associations

Location strongly influences presentation. Middle cranial fossa cysts are the classic “incidental” subtype (often left-sided) but can cause temporal lobe compression or seizures if large. Posterior fossa cysts can affect the cerebellum and fourth ventricle, producing ataxia or hydrocephalus. Suprasellar cysts can compress the optic chiasm and hypothalamic–pituitary region, leading to visual symptoms or endocrine issues.

- Middle cranial fossa (temporal region): most common; may cause headache, seizures, temporal lobe compression.

- Posterior fossa: may cause imbalance/ataxia, cranial nerve symptoms, or hydrocephalus.

- Suprasellar region: visual disturbance, hydrocephalus; consider endocrine effects if pituitary/hypothalamus involved.

- Convexity/interhemispheric: symptoms depend on mass effect; often incidental.

🩻 Imaging Findings (CT and MRI)

Arachnoid cysts mimic CSF on all standard sequences: they are well circumscribed, extra-axial, and do not behave like tumours or abscesses. They typically do not enhance with contrast and show no restricted diffusion. If large, they can cause mass effect (sulcal effacement, ventricular compression, midline shift) but classically show no surrounding vasogenic oedema. Key differentials include epidermoid cyst (diffusion restriction), porencephalic cyst (parenchymal loss/communication with ventricle), and chronic subdural collections (different signal characteristics and clinical context).

- CT: CSF density (hypodense), smooth margins, extra-axial; may remodel bone if longstanding.

- MRI T1: low signal (like CSF).

- MRI T2: high signal (like CSF).

- FLAIR: usually suppressed (like CSF); incomplete suppression suggests alternative diagnosis.

- DWI: no restricted diffusion (helps distinguish from epidermoid).

- Post-contrast: no enhancement.

- Mass effect: possible if large; typically no surrounding oedema.

🔎 Key Differentials (Imaging Pearls)

When a “CSF-like” lesion is seen, diffusion and anatomical context do most of the diagnostic work. Epidermoid cysts can look like CSF on T1/T2 but are “dirty” on FLAIR and classically restrict diffusion. Porencephalic cysts represent encephalomalacia with a cavity that communicates with ventricle/subarachnoid space and is associated with adjacent parenchymal volume loss. Chronic subdural hygromas/collections are extra-axial but conform to the convexity and fit clinical history (trauma, anticoagulation) more closely.

- Epidermoid cyst: CSF-like on T1/T2 but restricted diffusion; often incomplete FLAIR suppression.

- Porencephalic cyst: due to prior injury; parenchymal loss, gliosis, ventricular communication.

- Chronic subdural hygroma: crescentic extra-axial fluid; clinical trauma context; can evolve.

- Cystic tumours: mural nodule or enhancement raises concern; not pure CSF signal.

🧠 Clinical Presentation

Most arachnoid cysts are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. When symptomatic, symptoms reflect location and mass effect rather than “intrinsic” tissue destruction. Headache is the commonest symptom but is often non-specific; causal attribution is strongest when there is clear mass effect, hydrocephalus, or a tight correlation between symptom pattern and cyst location (e.g., progressive visual symptoms with suprasellar cyst). Seizures can occur, particularly with temporal region cysts, though causality varies and epilepsy work-up should remain standard.

- Incidental: common; no neurological deficit; stable cyst on follow-up.

- Headache: common but non-specific; more suggestive if hydrocephalus or clear mass effect present.

- Seizures: especially temporal/middle cranial fossa; evaluate as per epilepsy pathways.

- Focal deficits: weakness, language disturbance, cranial nerve symptoms if compressive.

- Hydrocephalus symptoms: vomiting, drowsiness, papilloedema, gait disturbance (site dependent).

- Children: macrocephaly, developmental delay, irritability (when large/expanding).

🚨 Red Flags (Urgent Action)

Urgent escalation is needed if there is evidence of raised intracranial pressure, acute neurological deterioration, or suspected cyst complication (e.g., rupture causing subdural hygroma/haemorrhage). Posterior fossa and suprasellar cysts deserve extra caution because they can compromise CSF pathways and vital structures. In these scenarios, urgent neuroimaging review and neurosurgical discussion are appropriate.

- Reduced consciousness, new confusion, or rapid deterioration.

- Persistent vomiting, severe progressive headache, papilloedema (raised ICP).

- Acute focal deficit or new cranial nerve palsy.

- Hydrocephalus on imaging.

- Suspected haemorrhage or new subdural collection after minor trauma.

🧯 Complications

Most cysts do not cause complications, but recognised issues include mass effect, hydrocephalus, and the (uncommon) development of subdural hygroma or haematoma—sometimes after trivial trauma—particularly with large middle cranial fossa cysts. Rarely, cyst rupture can cause acute symptoms. Bone remodelling (scalloping) can occur with longstanding pressure but is not malignant.

- Hydrocephalus: obstructed CSF pathways, particularly suprasellar/posterior fossa.

- Subdural hygroma: CSF leakage/pressure effects; may cause headache or focal symptoms.

- Subdural haematoma: risk can be increased with large cysts and minor trauma.

- Progressive mass effect: worsening deficits if cyst enlarges.

🧭 Management (Practical Approach)

Management depends on symptoms and objective evidence of cyst effect. Asymptomatic cysts usually need reassurance and either no follow-up or a single interval scan depending on age, size, and local practice. Symptomatic cysts require careful assessment to avoid misattributing common symptoms (like tension-type headache) to an incidental lesion; the strongest indications for neurosurgical referral are hydrocephalus, progressive neurological deficit, clear mass effect with symptom correlation, or recurrent cyst-related complications.

- Incidental/asymptomatic: reassure; consider interval imaging if large, atypical, or in children (local protocol).

- Symptomatic but unclear causality: assess for alternative causes (migraine, tension headache, vestibular disorders, epilepsy work-up); discuss with neurology/neurosurgery if uncertainty persists.

- Definite compressive effect: neurosurgical referral (mass effect with correlating symptoms, hydrocephalus, progressive deficit).

- Acute deterioration: urgent imaging review and neurosurgical escalation.

🛠️ Neurosurgical Options (When Indicated)

When intervention is needed, the goal is to relieve mass effect and restore CSF dynamics. Common strategies include endoscopic fenestration (creating communication with cisterns/ventricles), microsurgical fenestration, or cystoperitoneal shunting in selected cases. Choice depends on cyst location, anatomy, surgeon preference, and recurrence risk; fenestration is often preferred where anatomy allows because it avoids lifelong shunt dependence.

- Endoscopic fenestration: minimally invasive; creates opening into cistern/ventricle to equalise pressure.

- Microsurgical fenestration: more direct control; used for complex anatomy or difficult endoscopic access.

- Cystoperitoneal shunt: option when fenestration is not feasible or if recurrence persists; carries shunt-related risks.

📈 Prognosis and Follow-up

Prognosis is usually excellent. Many cysts remain stable for years and never cause problems. In symptomatic cases with clear mass effect or hydrocephalus, appropriate surgical intervention can improve symptoms, though headaches and seizures may not fully resolve if multifactorial. Follow-up strategy should be individualised by age, cyst size/location, symptoms, and local neurosurgical guidance.

- Most remain stable and never require intervention.

- Best surgical responders: hydrocephalus or objective mass effect with symptom correlation.

- Headache/seizures: may improve, but ensure standard headache/epilepsy management continues.

- Children: closer follow-up if large or if head growth/developmental concerns.

Categories

- A Level

- About

- Acute Medicine

- Anaesthetics and Critical Care

- Anatomy

- Biochemistry

- Book

- Cardiology

- Collections

- CompSci

- Crib Sheets

- Dental

- Dermatology

- Differentials

- Drugs

- ENT

- Education

- Electrocardiogram

- Embryology

- Emergency Medicine

- Endocrinology

- Ethics

- Foundation Doctors

- GCSE

- Gastroenterology

- General Practice

- Genetics

- Geriatric Medicine

- Guidelines

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Hepatology

- Immunology

- Infectious Diseases

- Infographic

- Investigations

- Lists

- Mandatory Training

- Medical Students

- Microbiology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Neurosurgery

- Nutrition

- OSCE

- Obstetrics

- Obstetrics Gynaecology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Oral Medicine and Dentistry

- Orthopaedics

- Paediatrics

- Palliative

- Pathology

- Pharmacology

- Physiology

- Procedures

- Psychiatry

- Public Health

- Radiology

- Renal

- Respiratory

- Resuscitation

- Revision

- Rheumatology

- Statistics and Research

- Stroke

- Surgery

- Toxicology

- Trauma and Orthopaedics

- USMLE

- Urology

- Vascular Surgery