Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

The Nephron – the Functional Unit of the Kidney

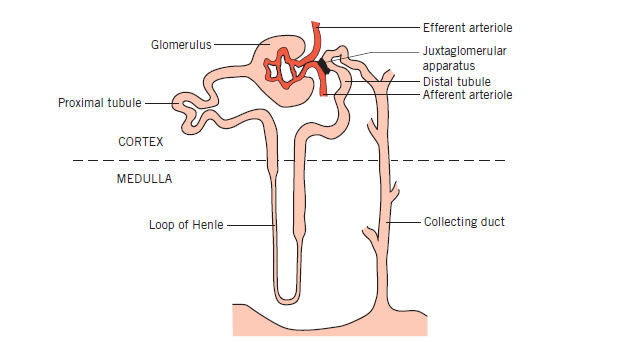

Each kidney contains ~1 million nephrons, and together they determine how the body handles water, electrolytes, acid–base balance, and waste. Think of the nephron as a highly regulated filtration–reabsorption–secretion system rather than a simple filter. Small changes in tubular transport have large systemic effects, which is why nephron physiology underpins hypertension, AKI, CKD, and many drug effects. Understanding where processes occur in the nephron helps you predict lab abnormalities and drug actions.

🩸 Renal Corpuscle: Glomerulus + Bowman’s Capsule

Blood enters via the afferent arteriole into the glomerular capillary tuft, where filtration occurs under hydrostatic pressure. The filtration barrier (fenestrated endothelium, basement membrane, podocytes) is size- and charge-selective, retaining cells and most proteins. Damage here explains proteinuria and haematuria in glomerulonephritis. Efferent arteriole tone is critical: constriction increases filtration pressure but risks downstream ischaemia.

- Filters ~180 L/day of plasma ultrafiltrate

- Proteins usually retained → proteinuria = pathology

🔄 Proximal Convoluted Tubule (PCT)

The PCT reabsorbs ~65–70% of filtered sodium and water, making it the workhorse of the nephron. Reabsorption here is largely iso-osmotic and driven by the Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase on the basolateral membrane. Glucose, amino acids, phosphate, and bicarbonate are reclaimed here—so PCT dysfunction causes glycosuria with normal blood glucose. This explains why SGLT2 inhibitors act here and cause mild osmotic diuresis.

- Reabsorbs all glucose (until transporters saturated)

- Major site of bicarbonate reclamation

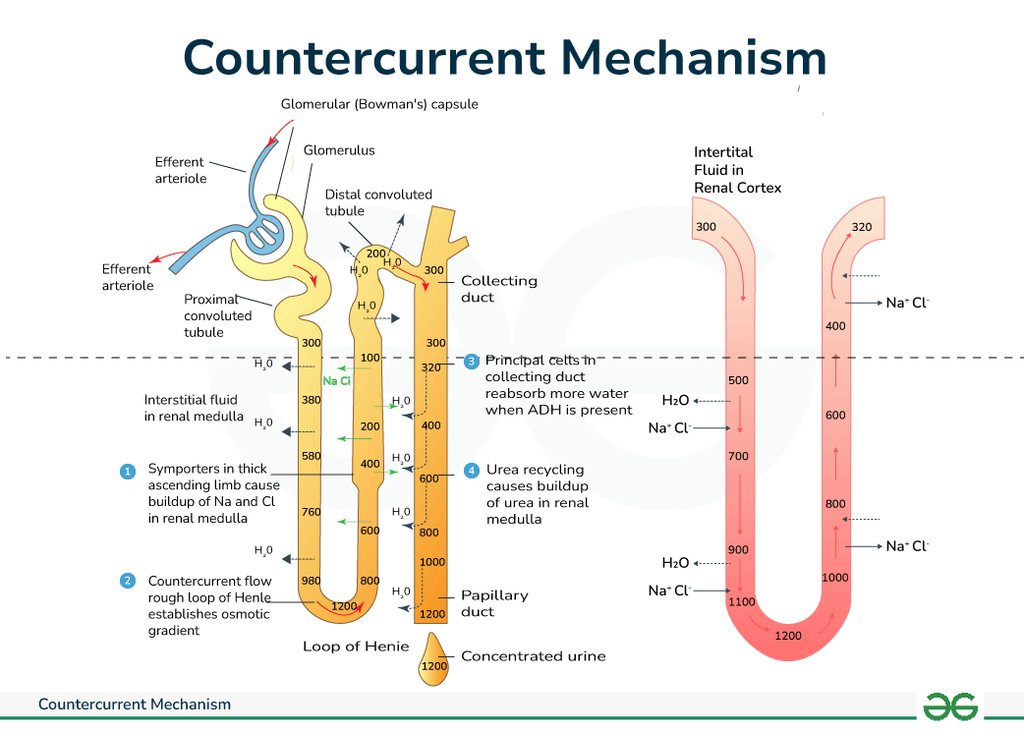

❄️ Loop of Henle

The loop of Henle creates the corticomedullary osmotic gradient via countercurrent multiplication. The descending limb is water-permeable but solute-poor, while the ascending limb pumps out Na⁺/K⁺/Cl⁻ and is water-impermeable. This separation of salt and water handling is essential for urine concentration. Loop diuretics act here, collapsing the gradient and producing potent diuresis.

- Descending limb: water out

- Ascending limb: salt out, no water

⚙️ Distal Convoluted Tubule (DCT)

The DCT fine-tunes electrolyte balance, particularly sodium, potassium, and calcium. Calcium reabsorption here is regulated by PTH, explaining hypercalcaemia risk with thiazide diuretics. This segment is less about bulk flow and more about regulation. Errors here present subtly but matter greatly in chronic electrolyte disorders.

- Site of thiazide diuretic action

- Important for calcium homeostasis

🚰 Collecting Duct

The collecting duct is hormonally controlled and determines final urine concentration. ADH increases water permeability via aquaporins, while aldosterone promotes sodium reabsorption and potassium secretion. This explains polyuria in diabetes insipidus and hyperkalaemia in hypoaldosteronism. Acid–base balance is also regulated here via intercalated cells.

- ADH → water reabsorption

- Aldosterone → Na⁺ retention, K⁺ loss

🧠 Clinical Pearl

When interpreting renal bloods, always ask: is the problem filtration (glomerulus), bulk handling (PCT/loop), or fine regulation (DCT/collecting duct)? This anatomical reasoning turns physiology into a diagnostic tool rather than rote learning. It’s also the key to understanding why different diuretics, toxins, and diseases produce distinct biochemical patterns.

Categories

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology