| Download the amazing global Makindo app: Android | Apple | |

|---|---|

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: Educational use only. Not for diagnosis or management. See below for full disclaimer. |

Arterial blood gas sampling

📌 Note: ABG sampling, particularly from the radial artery, can be painful. Offer 1 ml of 1% lidocaine at the puncture site to reduce pain without altering results.

Indications

- Assessment of respiratory failure and guiding therapy.

- Post-cardiac arrest management (baseline and ongoing monitoring).

- Acid–base assessment in critically unwell patients.

What ABG Provides

- pH (acid–base balance).

- Partial pressure of oxygen (PaO₂).

- Partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO₂).

- Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻).

- Base excess and calculated anion gap.

Preparation

- Wait 15–20 minutes after any O₂ therapy change for steady state.

- Explain procedure, risks (pain, bleeding, thrombosis, infection).

- Gain consent. Consider chaperone.

Contraindications

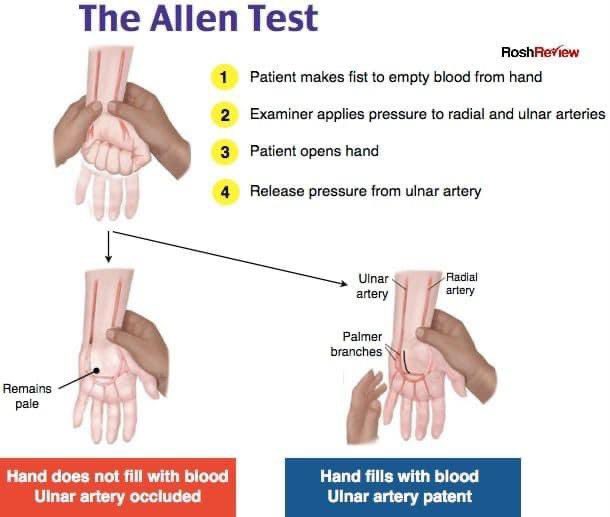

- Poor collateral circulation (check with modified Allen test).

- Severe coagulopathy or anticoagulation (relative).

- Severe peripheral vascular disease.

Equipment

- 2–3 ml heparinised syringe with cap.

- 20–22G needle (radial); larger for femoral access.

- Antiseptic wipes, gauze, tape, sterile gloves.

- Sharps bin.

Procedure

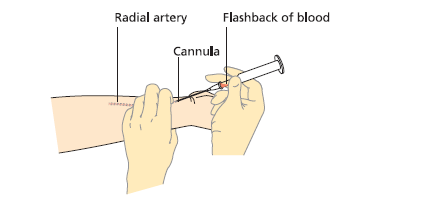

- Wash hands, wear gloves, explain to patient.

- Identify radial artery. Perform modified Allen test.

- Position wrist extended, palm up. Palpate pulse.

- Clean site with antiseptic.

- Expel excess heparin from syringe. Insert needle at 30–45° (bevel up).

- Bright red blood should pulsate into syringe under pressure.

- Obtain 1–3 ml, then withdraw needle and apply firm pressure ≥5 min (longer if anticoagulated).

- Cap syringe, remove air bubbles, send sample rapidly (on ice if delay).

- Document FiO₂ at time of sampling.

Arterial vs Venous Blood

- Arterial: bright red, fills syringe under pressure.

- Venous: darker, slow flow, may require suction.

Normal Ranges

- pH: 7.35 – 7.45

- PaO₂: 11 – 13 kPa (82 – 97 mmHg)

- PaCO₂: 4.7 – 6.0 kPa (35 – 45 mmHg)

- HCO₃⁻: 22 – 26 mmol/L

- Base excess: –2 to +2

- Anion gap: 8 – 12 (without K⁺)

Stepwise Interpretation

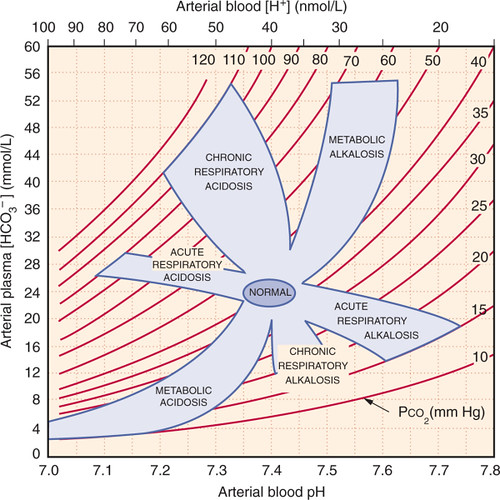

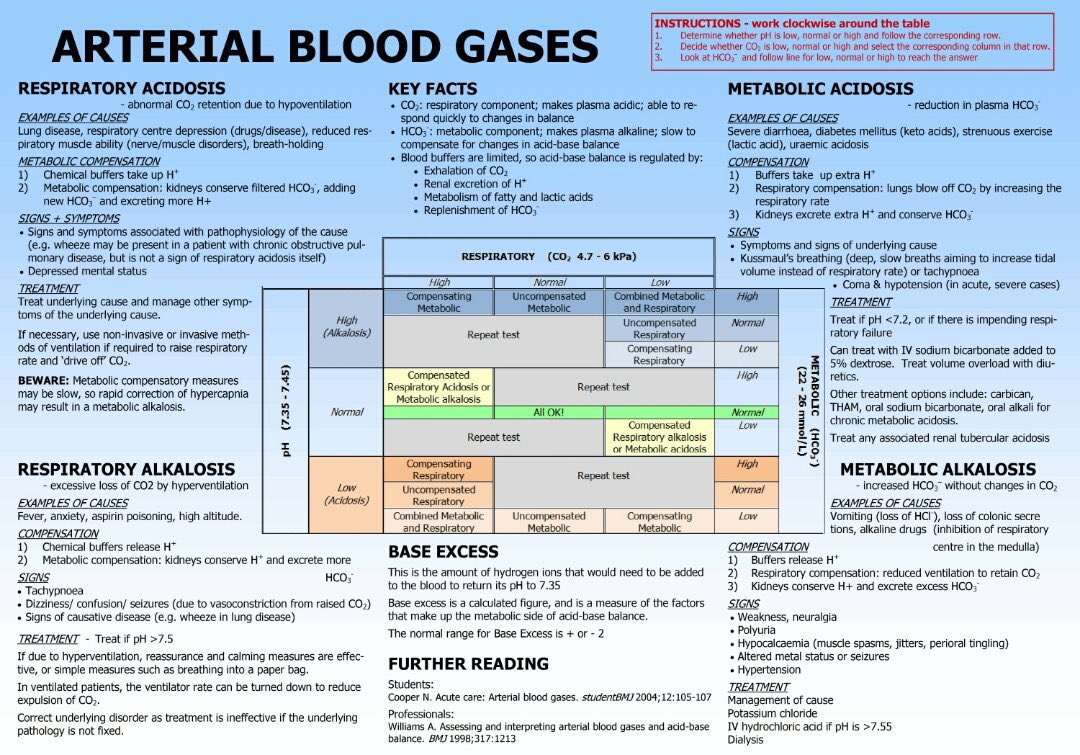

- Check pH: acidaemia (<7.35) or alkalaemia (>7.45)?

- Identify primary process:

- Low HCO₃⁻ → metabolic acidosis.

- High HCO₃⁻ → metabolic alkalosis.

- High PaCO₂ → respiratory acidosis.

- Low PaCO₂ → respiratory alkalosis.

- Check compensation:

- Metabolic acidosis → Winter’s formula: PaCO₂ ≈ 1.5 × HCO₃⁻ + 8 (±2).

- Metabolic alkalosis → PaCO₂ ≈ 0.7 × (HCO₃⁻ – 24) + 40.

- Acute resp. acidosis: HCO₃⁻ ↑ ~1 per 10 PaCO₂ ↑.

- Chronic resp. acidosis: HCO₃⁻ ↑ ~3–4 per 10 PaCO₂ ↑.

- Acute resp. alkalosis: HCO₃⁻ ↓ ~2 per 10 PaCO₂ ↓.

- Chronic resp. alkalosis: HCO₃⁻ ↓ ~4–5 per 10 PaCO₂ ↓.

- If metabolic acidosis: calculate anion gap.

- High AG → DKA, lactic acidosis, uraemia, toxins (methanol, ethylene glycol, salicylates).

- Normal AG → diarrhoea, renal tubular acidosis, saline excess.

- Match to clinical context.

Common Patterns & Causes

- Metabolic acidosis: DKA, sepsis/lactate, renal failure, diarrhoea.

- Metabolic alkalosis: vomiting, NG losses, diuretics, hyperaldosteronism.

- Respiratory acidosis: COPD exacerbation, opiates, severe asthma, neuromuscular disease.

- Respiratory alkalosis: anxiety, sepsis, pregnancy, pulmonary embolism.

Teaching Pearls

- Always record FiO₂ with the ABG.

- VBG useful for acid–base trend; ABG required for oxygenation.

- Lactate guides sepsis resuscitation.

- Correct AG for low albumin: each 10 g/L drop ↓ AG by ~2.5–3.

Related topics: Metabolic Acidosis | ABG Analysis