| Download the amazing global Makindo app: Android | Apple | |

|---|---|

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: Educational use only. Not for diagnosis or management. See below for full disclaimer. |

Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT)

Related Subjects: |Iron deficiency Anaemia |Haemolytic anaemia |Macrocytic anaemia |Megaloblastic anaemia |Microcytic anaemia |Myelodysplasia |Myelofibrosis |Hereditary Spherocytosis |Hereditary Elliptocytosis

🧬 Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler–Weber–Rendu disease, is a rare autosomal dominant vascular disorder. It causes fragile blood vessels (telangiectasias and AVMs) prone to bleeding, affecting the skin, mucous membranes, lungs, liver, and brain. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent serious complications such as GI bleeding, haemorrhagic stroke, and paradoxical emboli.

📖 About

- Definition: Genetic disorder causing abnormal blood vessel formation (telangiectasia, AVMs).

- Inheritance: Autosomal dominant - only one abnormal gene needed to manifest 👪.

- Sites involved: Skin, mucous membranes, lungs, liver, brain 🧠.

- Family history: Common; many affected individuals have a first-degree relative.

- Prevalence: ~1 in 5,000–8,000 worldwide 🌍.

🔎 Brain AVMs occur in ~10% of HHT patients, while pulmonary AVMs (PAVMs) are present in the majority. Screening for AVMs is critical to prevent life-threatening complications.

🧬 Aetiology

- Disorder of angiogenesis → malformed, fragile vessels.

- Genes: ENG (HHT1), ACVRL1 (HHT2), SMAD4 (HHT/Juvenile Polyposis overlap).

- Genotype–phenotype correlation:

- HHT1: ENG mutation, ↑ risk of brain AVMs (13%).

- HHT2: ACVRL1 mutation, lower brain AVM risk (2%).

- SMAD4: Associated with GI polyposis + HHT.

🧠 Stroke Mechanisms in HHT

- 💥 Haemorrhage from ruptured cerebral AVMs.

- 🫀 Paradoxical emboli via pulmonary AVMs → ischaemic stroke.

- 🩸 Fragility of GI vessels → severe GI bleeds & anaemia.

⚡ Clinical Features

- 👃 Epistaxis: Recurrent nosebleeds (most common).

- 🩸 GI bleeding: Haematemesis, melaena, iron deficiency anaemia (esp. >50 yrs).

- 🧠 Neurological: Haemorrhagic stroke (cerebral AVMs), embolic stroke (PAVMs).

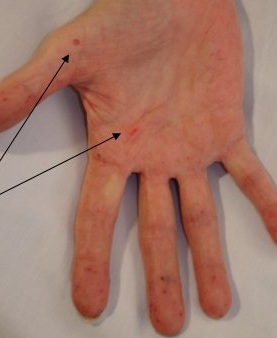

- 🩺 Mucocutaneous telangiectasia: Lips, oral cavity, nose, fingertips.

- 🫁 Pulmonary AVMs: Can rupture → haemoptysis, hypoxaemia.

📸 Clinical Signs

📊 Diagnostic Criteria (Curaçao Criteria)

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Epistaxis | Spontaneous, recurrent nosebleeds 👃. |

| Mucocutaneous Telangiectasia | Lips, oral cavity, fingers, nose - blanchable pink-red spots 🔴. |

| Visceral AVMs | Pulmonary, cerebral, hepatic, GI, spinal. |

| Family History | First-degree relative with confirmed HHT. |

✅ Definite HHT: ≥3 criteria ⚠️ Possible: 2 criteria ❌ Unlikely: <2 criteria

🔬 Investigations

- Bloods: FBC, ferritin, iron studies, B12/folate.

- Brain: MRI/MRA for AVMs.

- Lungs: Bubble echocardiogram (screening), CT pulmonary angiogram if positive 🫁.

- GI tract: Endoscopy/colonoscopy ± capsule endoscopy.

- Genetic testing: Confirms subtype, guides family screening 👪.

🩺 Management

- Emergency: ABC resuscitation, transfusions, urgent intervention for GI bleed or haemorrhagic stroke 🚑.

- Epistaxis: ENT laser ablation, cautery, nasal packing 👃.

- GI Bleeds: Iron replacement, endoscopic therapy 🍽️.

- Pulmonary AVMs: Embolization via interventional radiology 🫁.

- Medical: Antifibrinolytics (tranexamic acid), avoid antithrombotics 🚫.

- Genetics: Genetic counselling for families 🧬.

📈 Prognosis

- Chronic but variable disease course.

- Many lead normal lives with treatment ✅.

- Complications: GI bleeding, haemorrhagic stroke, embolic stroke.

- Early screening & treatment of AVMs improves long-term outcomes 🌱.