| Download the amazing global Makindo app: Android | Apple | |

|---|---|

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: Educational use only. Not for diagnosis or management. See below for full disclaimer. |

Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES)

Related Subjects: |Transverse myelitis |Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis |Cervical spondylosis |Spinal Cord Anatomy |Acute Disc Prolapse |Spinal Cord Compression |Spinal Cord Haematoma |Foix-Alajouanine syndrome |Cauda Equina |Conus Medullaris syndrome |Anterior Spinal Cord syndrome |Central Spinal Cord syndrome |Brown-Sequard Spinal Cord syndrome

🧠 Introduction

A patient presenting with acute low back pain together with bladder or bowel dysfunction and/or saddle sensory loss must be assumed to have Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES) until proven otherwise. The cauda equina begins below the spinal cord (which ends at L1) and contains lower motor neuron (LMN) fibres from lumbar and sacral roots — supplying the legs, perineum, and sphincters. Because these are LMN fibres, UMN signs are absent unless the spinal cord itself is involved. The most common cause is a large central lumbar disc prolapse at L4/5. Other causes include spinal fractures, postoperative epidural haematoma, stenosis, tumours, infection, or vascular occlusion.

📚 About

- CES results from compression of nerve roots below the L1/L2 level where the spinal cord ends.

- The cauda equina contains motor, sensory, and autonomic fibres — affecting limb power, sensation, bladder, bowel, and sexual function.

- Most commonly caused by a prolapsed intervertebral disc, but may arise from any mass effect in the lumbar canal.

- It represents a compressive radiculopathy involving multiple nerve roots.

💡 Teaching tip: The cauda equina lacks the protective epineurium and perineurium layers found in peripheral nerves, leaving these roots especially vulnerable to pressure injury.

🩺 Aetiology

- Central lumbar disc herniation (L4/5 or L5/S1) – most frequent cause.

- Degenerative spinal stenosis – canal narrowing in older adults.

- Spinal fractures or dislocations causing root compression.

- Spinal tumours – metastatic or primary (e.g. ependymoma, schwannoma).

- Postoperative haematoma or epidural abscess.

- AV malformations or dural fistulas leading to venous congestion or bleeding.

- Lipoma with spina bifida or congenital canal narrowing.

- Vascular occlusion from aortic dissection or aneurysm.

⚠️ The most common cause of urinary difficulty in degenerative lumbar disease is pain-related retention, not CES — but pain never excludes CES.

🚨 Clinical Features

- Severe bilateral sciatica or back pain, often acute in onset.

- Bladder dysfunction – urinary retention with overflow or loss of desire to void.

- Bowel dysfunction – faecal incontinence or constipation.

- Loss of perianal and saddle sensation – hallmark sign.

- Flaccid LMN weakness in the legs knocking out multiple lumbosacral roots (L3–S4); areflexia or reduced ankle jerks.

- L3–L4 (knee extension) – Quadriceps → difficulty rising from a chair, climbing stairs, giving way at the knee.

- L4–L5 (ankle dorsiflexion) – Tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus → foot drop, tripping over toes, difficulty heel-walking.

- L5–S1 (ankle eversion/inversion, toe movements, knee flexion) – Peronei, tibialis posterior, hamstrings, intrinsic foot muscles → weak push-off, unstable ankle, poor control of the foot.

- S1–S2 (plantarflexion) – Gastrocnemius–soleus → can’t tiptoe, weak plantarflexion, loss of ankle jerk.

- S2–S4 (sphincters and pelvic floor) – External anal sphincter, pelvic floor muscles, detrusor innervation → reduced anal tone, impaired voluntary squeeze, urinary retention/overflow, faecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction.

- this weakness is flaccid, asymmetrical and patchy, with areflexia and saddle anaesthesia

- Reduced anal tone and absent anal wink reflex.

- Sexual dysfunction due to autonomic involvement.

- No UMN signs – plantar responses down-going unless cord also compressed.

🦴 Anatomy

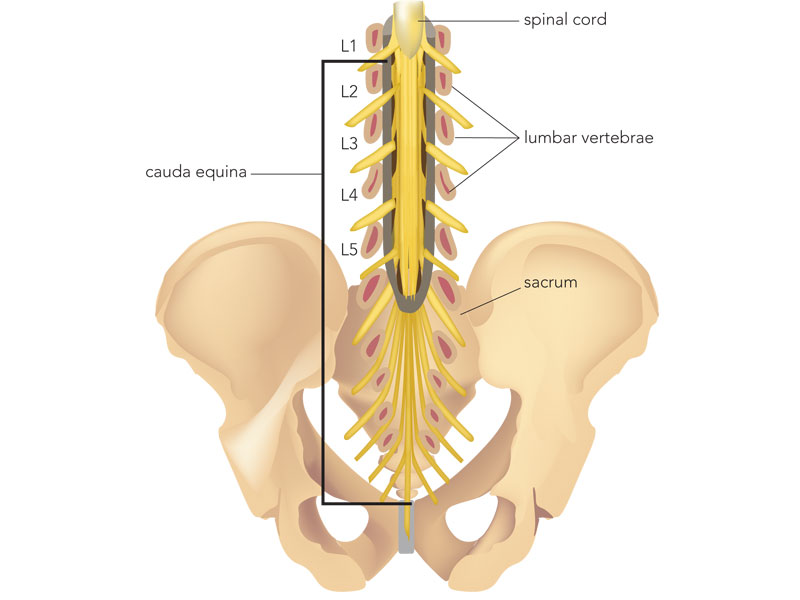

Figure 1: Anatomy of the lumbar spine showing the cauda equina below the L1 cord termination.

Figure 1: Anatomy of the lumbar spine showing the cauda equina below the L1 cord termination.

💥 Central Disc Compression

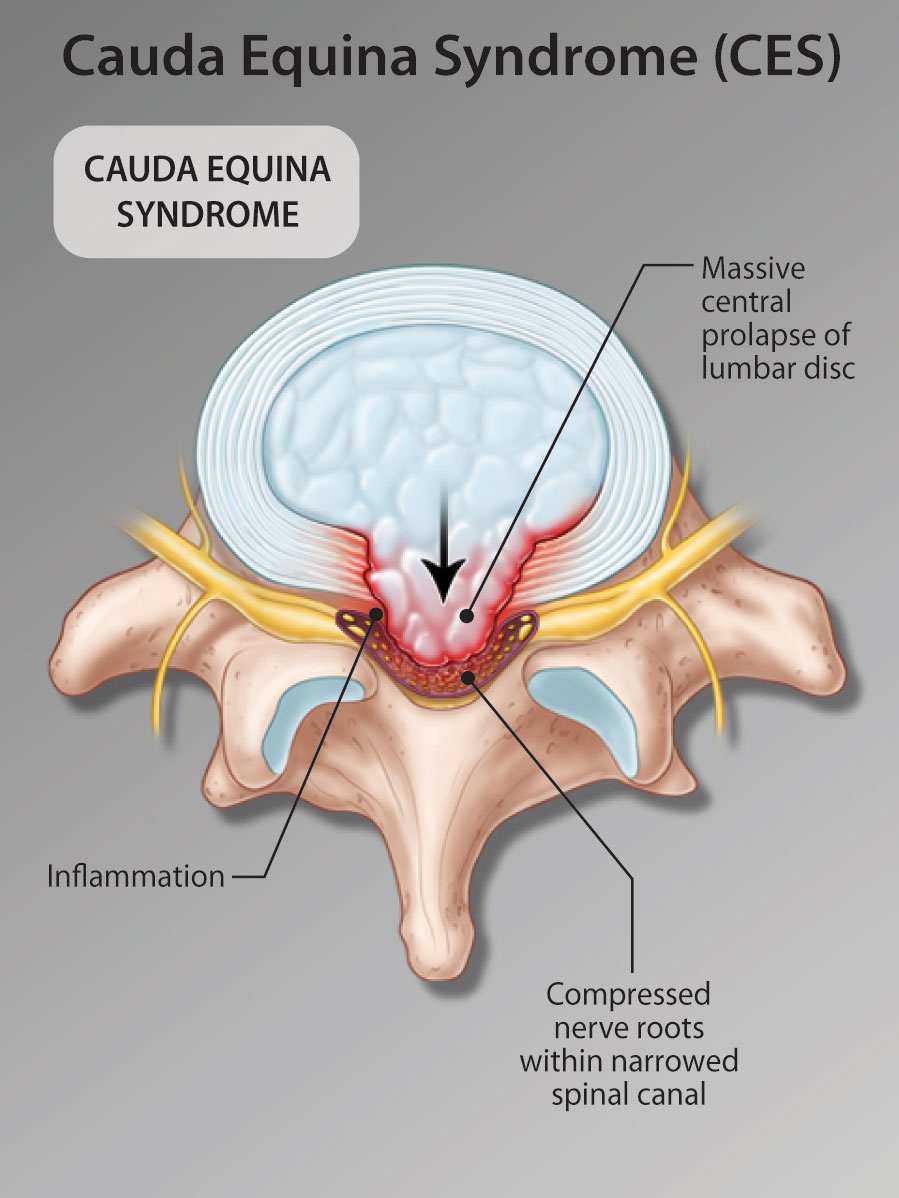

Figure 2: Central lumbar disc herniation compressing multiple nerve roots.

Figure 2: Central lumbar disc herniation compressing multiple nerve roots.

⚡ High-Risk (“Pre-CES”) Patients

- Bilateral radicular pain or sensory disturbance.

- Bilateral motor weakness or loss of reflexes.

- These patients may not yet have CES but are at high risk — urgent MRI is mandatory.

🔬 Investigations

- Bloods: FBC, U&E, CRP, ESR, calcium, PSA (if older male), and myeloma screen when indicated.

- Malignancy screening: Breast exam/mammogram; skin check for melanoma.

- Imaging:

- MRI spine (urgent): Gold standard to identify soft tissue compression.

- CT spine: If MRI contraindicated or unavailable — excellent for bone detail.

- USS bladder: May assess residual volume but cannot rule out CES.

- Plain X-rays: Rarely diagnostic.

- Neurological exam: Assess motor power, reflexes, perineal sensation, anal tone, and voluntary anal contraction.

🧩 The Four Stages of CES

- CESS – Suspected: Bilateral sciatica ± saddle paraesthesia but intact bladder function.

- CES I – Incomplete: Altered urinary sensation, poor stream, need to strain, loss of desire to void.

- CES R – Retention: Painless urinary retention and overflow incontinence.

- CES C – Complete: Loss of bladder/bowel control, absent perineal sensation, patulous anus, erectile dysfunction.

📊 Imaging Outcomes

- Compression confirmed: Immediate spinal referral for decompression (within 24 h).

- No compression: Review for alternative spinal pathology and warn about CES symptoms.

- Non-compressive pathology: e.g. demyelination → refer to neurology.

- Unexplained symptoms: Consider cervicothoracic MRI or continence referral.

⏱️ Timing is critical: Decompression within 24 hours of bladder or bowel involvement yields the best outcomes. Delay beyond 24 hours markedly increases risk of permanent dysfunction.

⚕️ Management

- CES is a neurosurgical emergency. Prompt MRI and spinal referral are vital for diagnosis and treatment.

- High-risk but incomplete CES: Urgent MRI; if large central disc found, proceed to decompression before progression.

- Confirmed CES: Emergency laminectomy and decompression, ideally within 24 hours (some guidelines allow 48 h).

- Rehabilitation: Early spinal rehab addressing mobility, bladder and bowel care, pain control, and sexual health.

- Long-term care: Many patients experience persistent neuropathic pain or sphincter dysfunction; multidisciplinary input is essential.

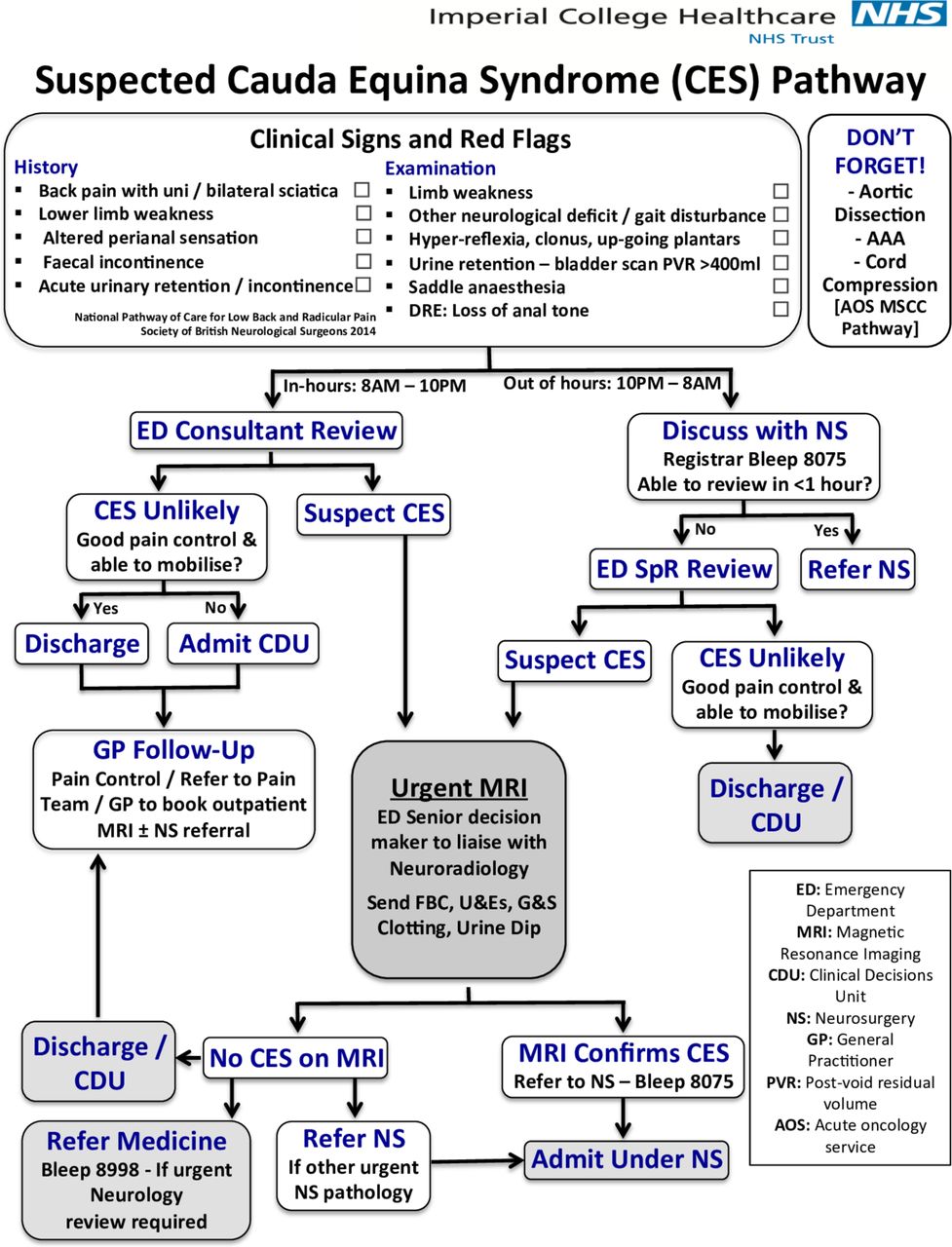

Figure 3: MRI demonstrating severe cauda equina compression requiring surgical decompression.

Figure 3: MRI demonstrating severe cauda equina compression requiring surgical decompression.

📚 References

- Greenhalgh S et al. (2018). Assessment and Management of Cauda Equina Syndrome. Musculoskeletal Science & Practice 37: 69–74.

- SBNS & BASS Standards of Care for Investigation and Management of CES (2018).

- Todd N V. (2009). An Algorithm for Suspected Cauda Equina Syndrome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 91(6): 414–418.