Makindo Medical Notes"One small step for man, one large step for Makindo" |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis, or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd. |

Cerebral Veins 🧠

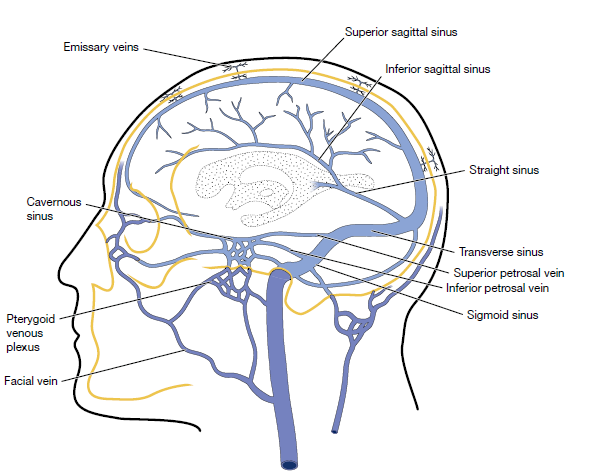

Cerebral venous drainage is a low-pressure, highly variable system responsible for returning deoxygenated blood from the brain to the heart. Unlike arterial supply, venous anatomy is asymmetric and more tolerant of obstruction, but failure of venous outflow can cause dramatic rises in intracranial pressure (ICP) and venous infarction. Understanding venous flow is particularly important when interpreting haemorrhagic stroke, raised ICP, and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST).

🔹 Superficial Cerebral Veins

Superficial veins drain the cerebral cortex and subcortical white matter. They run within the subarachnoid space and usually empty into the dural venous sinuses. Key superficial veins include the superior cerebral veins, which drain into the superior sagittal sinus, and the superficial middle cerebral vein, which often drains into the cavernous or sphenoparietal sinus.

- Drain cortex and superficial white matter

- Thin-walled and vulnerable to tearing (→ subdural haematoma)

- Highly variable anatomy between individuals

🔹 Deep Cerebral Veins

Deep veins drain the metabolically critical deep structures of the brain, including the thalami, basal ganglia, internal capsule, and deep white matter. The paired internal cerebral veins form from the union of the thalamostriate and choroidal veins and unite posteriorly to form the vein of Galen.

- Drain thalami, basal ganglia, deep white matter

- Internal cerebral veins → vein of Galen → straight sinus

- Deep venous thrombosis often causes bilateral lesions

🔹 Dural Venous Sinuses

Dural venous sinuses are rigid, endothelial-lined channels between layers of dura mater. Their rigidity prevents collapse and allows continuous venous drainage despite changes in ICP. Major sinuses include the superior sagittal, inferior sagittal, straight, transverse, sigmoid, and cavernous sinuses.

- No valves → bidirectional flow possible

- Drain into internal jugular veins

- Common sites for venous sinus thrombosis

🌊 Physiology of Cerebral Venous Flow

Cerebral venous flow is passive and pressure-dependent, driven by the gradient between cerebral capillary pressure and right atrial pressure. Any rise in central venous pressure, such as coughing, Valsalva manoeuvre, or right heart failure, can impair venous drainage and increase ICP. This explains why venous pathology often presents with headache and papilloedema.

⚠️ Clinical Relevance

Venous obstruction leads to impaired outflow, venous congestion, and reduced cerebral perfusion pressure. This can result in venous infarction, which characteristically becomes haemorrhagic due to capillary rupture. In the UK, CVST should be suspected in younger patients with headache, seizures, or atypical stroke patterns, especially with prothrombotic risk factors.

- CVST → headache, seizures, focal deficits

- Venous infarcts often haemorrhagic and non-arterial in distribution

- MR venography is the imaging modality of choice

🩺 Teaching Pearl

If a “stroke” does not respect an arterial territory, think venous. Bilateral thalamic involvement should immediately raise suspicion of deep venous system thrombosis. Venous disease is uncommon but exam-favourite and clinically high-stakes.

Categories

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology