| Download the amazing global Makindo app: Android | Apple | |

|---|---|

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER: Educational use only. Not for diagnosis or management. See below for full disclaimer. |

Haemorrhagic stroke

Related Subjects: |Subarachnoid Haemorrhage |Perimesencephalic Subarachnoid haemorrhage |Haemorrhagic stroke |Cerebellar Haemorrhage |Putaminal Haemorrhage |Thalamic Haemorrhage |ICH Classification and Severity Scores

🧠 Introduction

- Haemorrhagic stroke, also called Spontaneous Intracerebral Haemorrhage (SICH), is often sudden and devastating.

- Accounts for ~15% of all strokes (majority are ischaemic).

- One subtype is Subarachnoid Haemorrhage (SAH), usually from ruptured aneurysms or vascular anomalies (discussed separately).

- ⚠️ Mortality is high: 30–50% of patients with large bleeds die within 30 days.

- Smaller bleeds can have better outcomes → focus on identifying cause and preventing recurrence.

- ❌ Traumatic intracranial haemorrhage and extra-axial bleeds (subdural, extradural) are not classified as stroke.

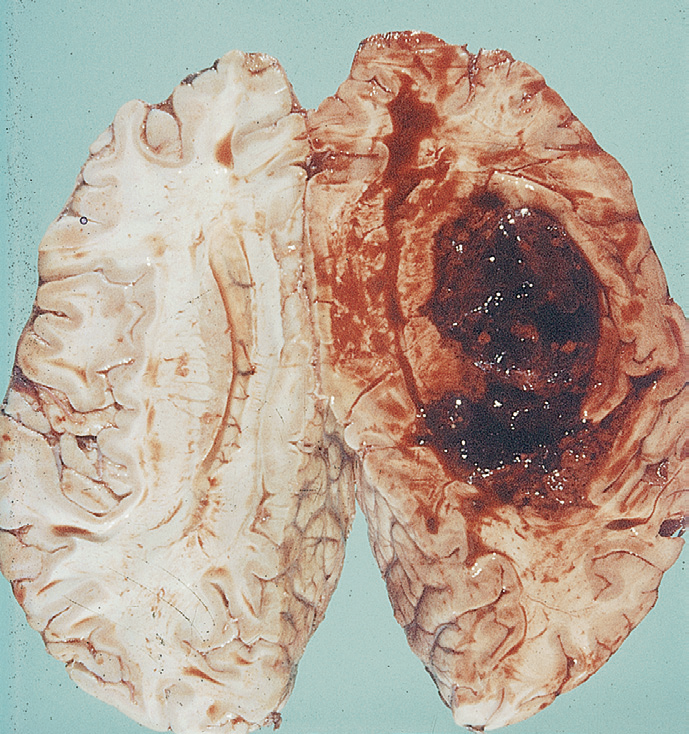

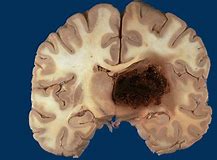

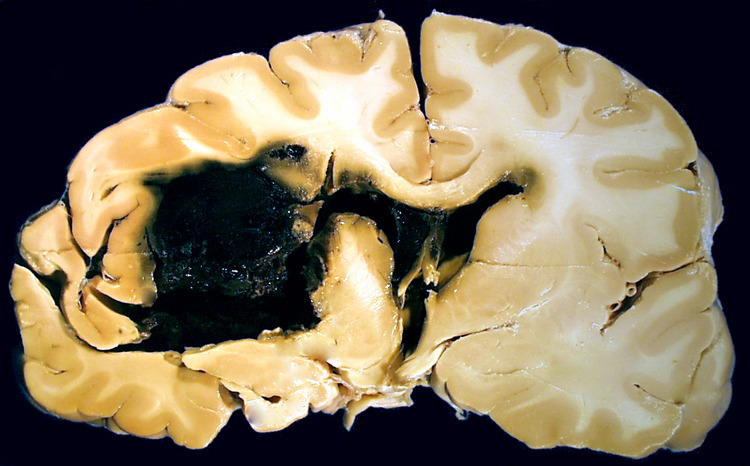

🔬 Pathological Appearance

On pathology and imaging, haemorrhagic strokes show destructive haematomas, surrounding oedema, and pressure effects:

⚙️ Aetiology

- Vessel rupture: Can occur anywhere from Circle of Willis arteries to small penetrating arterioles, capillaries, and draining veins.

- Aneurysms: Berry aneurysm rupture → high-pressure SAH.

- Small vessel disease: Hypertension → lipohyalinosis, Charcot–Bouchard microaneurysms → deep bleeds.

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: In elderly → lobar bleeds.

- Structural: AVMs, cavernomas, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia.

- Neoplastic: Tumours (esp. melanoma, RCC, thyroid, choriocarcinoma, lung) prone to bleed.

- Coagulopathies: Anticoagulants (warfarin, DOACs), antiplatelets, thrombocytopenia, haemophilia, liver disease.

- Venous sinus thrombosis: Back-pressure haemorrhage → paradoxically requires anticoagulation.

🌍 Epidemiology

- More common in Afro-Caribbean, South-East Asian, and Japanese populations.

- Strong association with hypertension prevalence and genetic predisposition (amyloid angiopathy).

🧾 Causes by Age Group

- 🧓 Elderly: Hypertension, cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

- 👩 Younger adults: AVMs, aneurysms, cavernomas, coagulopathies.

- 💊 Any age: Anticoagulation therapy, illicit drugs (cocaine, amphetamines).

🧭 Types by Anatomy

- 🧠 Lobar: Cortex ± subcortical white matter.

- ⚫ Deep: Putaminal, thalamic, caudate, basal ganglia.

- 🧩 Brainstem: Pontine haemorrhage → sudden coma, pinpoint pupils.

- 🌀 Cerebellar: Ataxia, vertigo; large bleeds (>3 cm) may need evacuation.

- 💥 Subarachnoid haemorrhage: Usually aneurysmal.

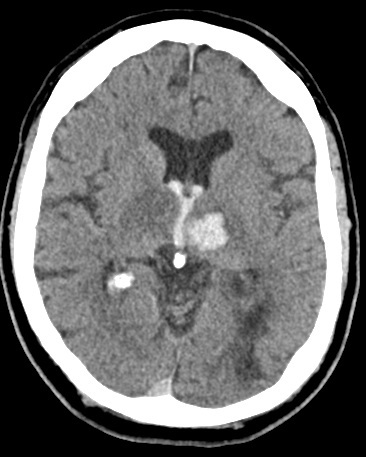

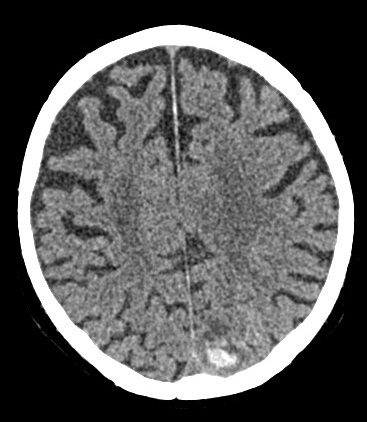

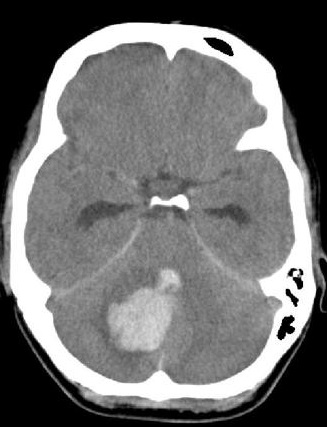

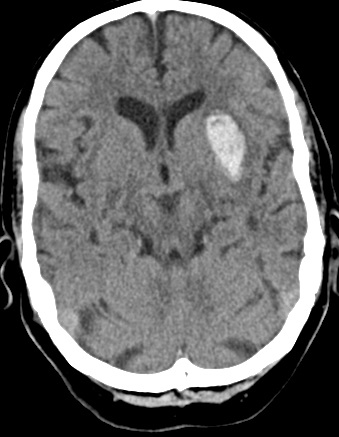

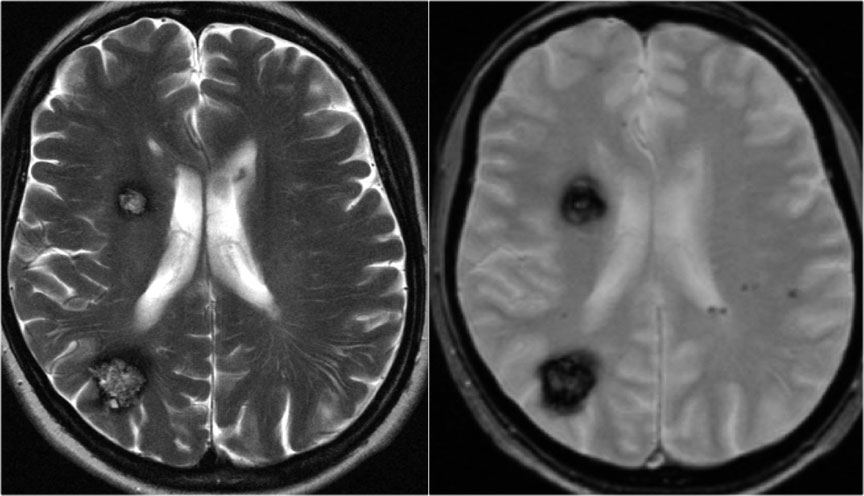

📸 Example Imaging

CT and MRI examples of haemorrhagic stroke:

🩺 Clinical Presentation

- 🧨 Sudden severe headache, vomiting, reduced consciousness.

- 🧑⚕️ Focal neurology: hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, aphasia, neglect, visual field deficits.

- 🌀 Cerebellar bleeds: vertigo, nausea, truncal ataxia, nystagmus.

- 🟣 Brainstem bleeds: coma, quadriplegia, miosis, “locked-in” syndrome.

- 🔦 SAH: Thunderclap headache, collapse, meningism, reduced GCS.

⚠️ Complications

- Intraventricular extension → acute deterioration, coma.

- Hydrocephalus from ventricular obstruction.

- Cerebral oedema, raised ICP, herniation (coning).

- Seizures (early or delayed).

- Rebleeding, especially in aneurysmal SAH and AVM.

🚩 Red Flags for Secondary Causes

- Age <50.

- No history of hypertension.

- Recurrent or atypical bleeds.

- Lobar location (esp. with soft tissue swelling or fracture → trauma vs primary bleed).

- Family history or features of inherited vascular syndromes (HHT).

🔍 Investigations

- 🩸 Bloods: FBC, U&E, LFT, glucose, coagulation, ESR/CRP.

- 🖼️ Non-contrast CT: First-line, detects haematoma, intraventricular blood, hydrocephalus.

- 🧲 MRI: Detects microbleeds, chronic haemosiderin, cavernomas (SWI/GRE).

- 📡 MRA/CTA: Aneurysms, AVMs, dissections.

- 🩻 MRV: Suspected venous sinus thrombosis.

- 📌 DSA: Gold standard for vascular malformations; small stroke risk.

- ❤️ Echocardiography: Endocarditis, embolic source.

- 💉 LP: For SAH if CT normal but suspicion high.

📊 Prognostic Scoring (ICH Score)

- GCS: 3–4 (+2), 5–12 (+1), 13–15 (0).

- Age ≥80: +1.

- Volume >30 ml: +1.

- Intraventricular haemorrhage: +1.

- Infratentorial location: +1.

➡️ Higher total = worse prognosis. 0 = 0%, 1 = 13%, 2 = 26%, 3 = 72%, 4 = 97%, 5 = 100% 30-day mortality.

⚖️ Management

- 🛑 Immediate: ABC, airway support, early CT, correct coagulopathy, cautious BP lowering, neurosurgical referral.

- 💊 Reverse anticoagulation: Warfarin INR>1.4 → Vit K + PCC (Octaplex). Stop DOAC/antiplatelets. Avoid platelets (PATCH trial).

- 📉 Blood pressure: Reduce to <160 systolic with IV agents (e.g. labetalol). Avoid hypoperfusion.

- 🧑⚕️ Neurosurgery: Consider clot evacuation, especially cerebellar bleeds >3 cm or deteriorating GCS. EVD for hydrocephalus.

- 💉 Seizure control: IV phenytoin/levetiracetam if seizures.

- 🧑🦽 Rehabilitation: MDT stroke/ICU team for survivors.

- ❌ Avoid: Routine mannitol (except bridging), steroids (harmful), unnecessary statin withdrawal without review.

📉 Prognosis

- Large bleeds, IVH, infratentorial location, and advanced age = worse outcomes.

- Many survivors are left with major neurological deficits.

💡 Exam Pearl: Intracerebral haemorrhage = sudden headache + neuro deficit + ↓ consciousness. ➡️ Early non-contrast CT is essential — clinical features alone cannot distinguish from ischaemic stroke.

Categories

- A Level

- About

- Acute Medicine

- Anaesthetics and Critical Care

- Anatomy

- Biochemistry

- Book

- Cardiology

- Collections

- CompSci

- Crib Sheets

- Dental

- Dermatology

- Differentials

- Drugs

- ENT

- Education

- Electrocardiogram

- Embryology

- Emergency Medicine

- Endocrinology

- Ethics

- Foundation Doctors

- GCSE

- Gastroenterology

- General Practice

- Genetics

- Geriatric Medicine

- Guidelines

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Hepatology

- Immunology

- Infectious Diseases

- Infographic

- Investigations

- Lists

- Mandatory Training

- Medical Students

- Microbiology

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Neurosurgery

- Nutrition

- OSCE

- OSCEs

- Obstetrics

- Obstetrics Gynaecology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Oral Medicine and Dentistry

- Orthopaedics

- Paediatrics

- Palliative

- Pathology

- Pharmacology

- Physiology

- Procedures

- Psychiatry

- Public Health

- Radiology

- Renal

- Respiratory

- Resuscitation

- Revision

- Rheumatology

- Statistics and Research

- Stroke

- Surgery

- Toxicology

- Trauma and Orthopaedics

- USMLE

- Urology

- Vascular Surgery